Rabbit Hole: Salisbury Mansion, SLC

A Deep Dive Into the History of The Creepy Building In My Neighborhood

In my neighborhood, near my apartment building, sits a perfect haunted house.

The Salisbury Mansion a stately 19th-century manor that has not been lived in for many years, and been left completely uninhabited for several more. It’s been disappointed by many promises of restoration, subject to graffiti and broken windows and trespassing teens. It waits there, dark and empty, watching me whenever I walk by. When friends leave my home at night, I wish them good luck as they walk past the haunted house.

The building is also markedly sad. Downton Salt Lake City is full of lovingly maintained or restored historical buildings. Built by settlers of early Salt Lake City, these mansions serve as testaments of wealth and proud reminders how the city rose up from humble pioneer beginnings. But this house is forgotten, its memories left to grow stale. The building is waiting, perched on the edge of a sigh. Prime real-estate for ghosts.

In his book Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, author Colin Dickey argues that the emergence of ghost stories is a way in which society attempts to deal with the dissonance created by a violation of our beliefs; a way in which we can explain away guilt, anxiety, and fear. “The past we’re most afraid to speak aloud of in the bright light of day is the same past that tends to linger in the ghost stories we whisper in the dark.” The Haunted House, Dickey writes, is “the American dream gone horribly wrong.” And so it is for this derelict building, once a prime example of pioneer industry and the promise of the American West. Now it serves as a stark reminder of how that American dream has failed. Surrounded by apartment buildings and near communities of unhoused people, the building sits in a neighborhood made up of the kind of people on whose backs the mansion was built.

The mansion was built in 1898 for a gentleman named Orange James Salisbury. It was designed by Frederick Albert Hale, a then-prominent architect who designed many Neo-classical buildings throughout Salt Lake City. The Salt Lake City Planning Commission lists the building’s original features, including :

a circular staircase, forming a small semi-circular apse on the West side of the building

two-story entrance portico topped with a triangular pediment gable roof supported by four ionic columns

bracketed swan’s neck pediment over doorway

masonry of cut sandstone from East Canyon, Utah

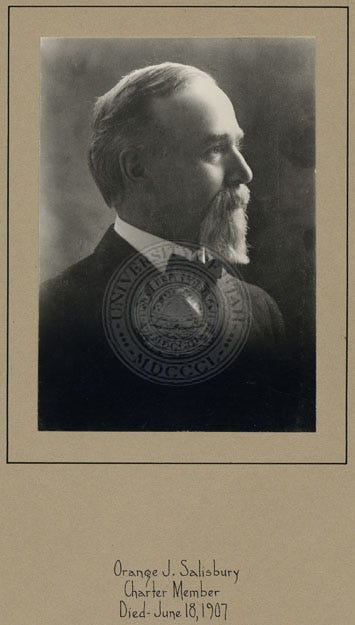

O.J. Salisbury was a true tycoon of the west. He co-founded Gilmer & Salisbury, a Stagecoach operation that stretched across seven states. He was a prominent investor in mines, and owned many properties, including banks and hotels, in Salt Lake City. He had the Salisbury Mansion built later in his life— it was finished in 1898 and he passed away in 1907.

Not much is known about O.J. Salisbury outside of his business and properties. He was married and had at least three children, perhaps more, and was born (and died) in New York. But one thing comes through quite clearly: his business was in and of the industrialist age, with all the predation that went along with it.

In a letter he wrote to a business associate in 1891, Salisbury discusses the trials of starting operations at a new mine in Idaho (from which ore was typically sent to Salt Lake City to smelt and sell). The letter reads like a stereotype of robber-barony industrialist practices. Money is tight, he says, and they need to take some drastic measures to get ore from the mine. “Put off every thing you possibly can until we get the [mine] running and commence getting returns on ores & bullion,” he instructs. “Put off the regular pay day until the 10th or 15th next month.”

How to get ore to sell when you can’t pay your regular workforce? Salisbury had a suggestion: “We want ore now, and the dead work can be done next winter. I think the Italians would be glad to put in a month or two by days work.” He explains that they can hire the Italians on contract, have them drill for enough ore for a good sale, and then they can send them on their way. “You understand, money is very close and hard to get and I don’t want you to keep a man around [the mines] more than is absolutely necessary to carry on the business.”

At the time, Italians were known as cheap labor. Epidemics, overpopulation, and economic woes pushes Italian people out of their home country and into the United States, where they were more often than not met with discrimination and mistreatment. According to the State of Utah’s Department of Cultural and Community Engagement, many of the Italian immigrants that settled in Utah were kept in poverty as they were paid in company scrip and lived on company land. When Italian miners went on strike, several companies in Utah announced they would no longer hire immigrants. Landlords refused to rent to Italians, leading to the creation of a long-forgotten “Little Italy” near Magna, UT, where the immigrants “lived in shacks they built themselves from boards… the shacks were not warm in the winter, and they did not keep out heat in the summer… They had no dishes and many of them only lived off milk and coffee.”

I don’t want to force a conclusion here; I don’t have enough information to draw a straight line from exploited workers to the Salisbury Manor. But I do believe that this context is important; the wealth exhibited in this beautiful mansion is not indicative of wealth alone. No matter if this was a one-time shortcut or a typical business practice for Salisbury, the mansion and the business it came from inevitably contains a darker story.

After Salisbury’s death in 1907, the home stayed in the family for a little while before becoming a wedding reception center/boarding house in 1927. In 1934, the manse was sold to Evans & Early Mortuary, who owned it into 2016.

I can’t find anything on Evans & Early Mortuary aside from old obituaries and a link that now redirects to a nationwide funeral home network. It feels strange that in the digital age, when nothing is truly gone, a 100-year-old business could seemingly dissipate into nothingness.

For those who had loved ones memorialized in the Salisbury Mansion, I wonder what they think as they drive by these days. What was once a place of beauty that offered support on sad days is now sad itself.

A short blog post from a real estate agent gives us a tiny glimpse into what the building was like as a mortuary. Jordan Smith of the Muve Real Estate group toured funeral home and took pictures, I’m guessing around the time Evans & Early was dissolved and the building was sold. Smith writes about his conversation with the (unnamed) long-time funeral director:

“He loves this building. That much is clear. If he is a ghost, he’s happy, and thoughtful. But he’s not a ghost. He’s a man who has poured his heart and soul into this historic mansion. He’s sat with families as they mourned the loss of loved ones. There’s nothing spooky in the corridors. It’s more spiritual. It’s filled with love and the celebration of life in its most precious moments. It’s heartbreaking, and it’s beautiful.”

The photographs accompanying this post portray a building already empty, frozen in time. An empty, antique wheelchair. Darkened rooms. An embalming table under fluorescent light.

A video posted by another real estate professional shows a building that, for all the lighting and flashy, quick-moving camera work, is odd in its emptiness. Such a house wasn’t meant to stand alone.

By 2017, the Salisbury Mansion was purchased by a local doctor, who filed for permits to begin renovations and construction on the home with the plan to turn it into an assisted living facility. Another one to add to the many in the area, which gives me conflicting feelings as, despite the extreme need for more elder care, assisted living facilities are too often the setting for abuse and neglect.

However, there’s no Salisbury Assisted Living facility in sight, despite the fact that the LLC is registered. The Salisbury Mansion has continued to sit empty— though far from untouched, as it’s been subject to decay and trespassing and mistreatment perhaps inevitable in the downtown area of a major city. In the two years I’ve lived in the neighborhood, the building has slowly gotten darker. More and more windows get broken and boarded up. The fences surrounding it get higher. The graffiti multiplies. The current owner’s construction plans were revised and again approved in 2021, and still… the building sits empty.

I’m not the only one concerned. As I was doing research, I discovered that Preservation Utah posted about the property just two days ago:

In recent days, we have received a large number of calls from people concerned about the historic Salisbury Mansion.

In 2017, Salt Lake City Landmarks Commission reviewed a proposal to transform the Salisbury mansion into an assisted living facility with 51 rooms and the children's daycare. This proposal was approved, but since then the mansion has decayed with little work done to maintain it. In a phone call made to the building's owners this past week, Preservation Utah confirmed that the plan is still to transform the Salisbury into a assisted living center. When asked about the time frame for this project, the owners stated they aim to start as soon as possible.

The creative, the romantic, the dreamer in me populates the mansion with ghosts. I look into the stained-glass porthole windows in the attic and think of faces looking back at me. Perhaps the exploited workers who built Salisbury’s fortune, or his family who once lived there, or a lost soul who was memorialized there and never found their way home.

But I also know that at least a portion of my feelings are part of the cycle of myth-making. I’m frustrated that my boyfriend and I trip over each other in my tiny apartment, that I rarely have friends over because they, frankly, wouldn’t fit in my home. I work my forty-hour-week and my obligatory millennial side-gigs without hope that I’ll ever be able to purchase a house of my own. My economic anxiety and political frustration use the Salisbury Mansion as an outlet— of course such a house is haunted! Because I believe such a house deserves it. “The archetypal haunted house story is fundamentally about class,” Colin Dickey writes in Ghostland. “The townspeople grow resentful because, by the force of economics, they are imprisoned by the rich and their folly.”

On the other hand, I see beauty in the spookiness of the old building. It’s a vestige of the old Salt Lake, not yet gentrified, and rich in the history of such a strange and wonderful city. “Park next to the haunted building,” I tell visitors with a mischievous grin. “It used to be a mortuary,” I say with childish delight. When my boyfriend and I walk by the stately old house, hand in hand, we look into the darkened windows and I wish for a glimpse of the supernatural. The building is weighed down by history, rich in potential, made magical by the possibility of the unknown.

It’s the perfect haunted house.

My grandmother grew up there.

Pretty much can fill in any blanks lol

She would find it amusing her childhood home was considered scary!!